Improving Safety Filter Integration for Enhanced Reinforcement Learning in Robotics

Abstract

Reinforcement learning (RL) controllers are flexible and performant but rarely guarantee safety. Safety filters impart hard safety guarantees to RL controllers while maintaining flexibility. However, safety filters cause undesired behaviours due to the separation of the controller and the safety filter, degrading performance and robustness. This extended abstract unifies two complementary approaches aimed at improving the integration between the safety filter and the RL controller. The first extends the objective horizon of a safety filter to minimize corrections over a longer horizon. The second incorporates safety filters into the training of RL controllers, improving sample efficiency and policy performance. Together, these methods improve the training and deployment of RL controllers while guaranteeing safety.

1 - Multi-Step Safety Filters

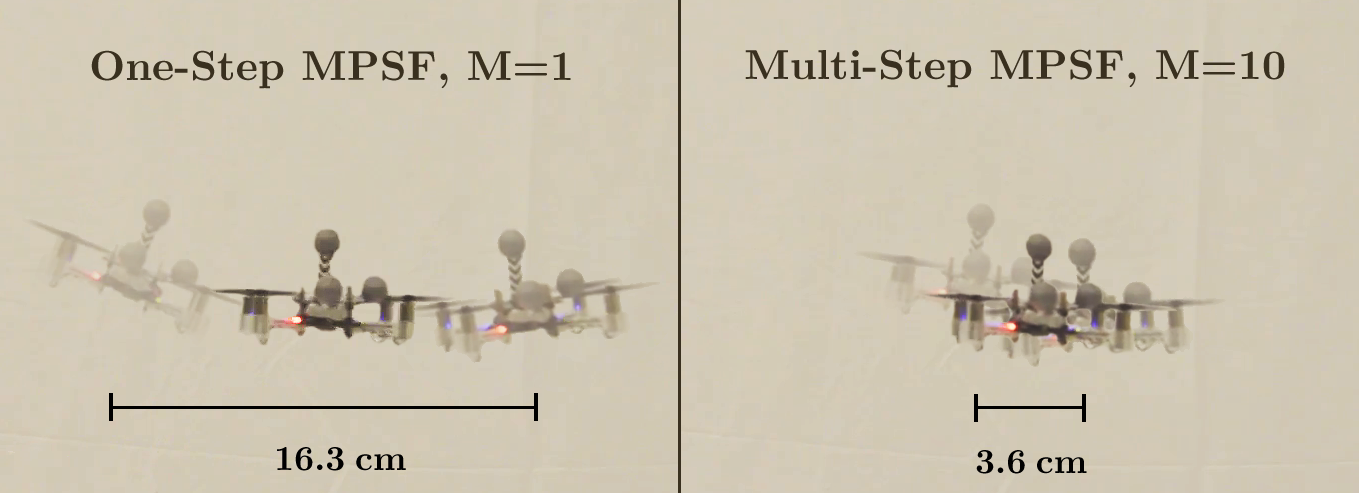

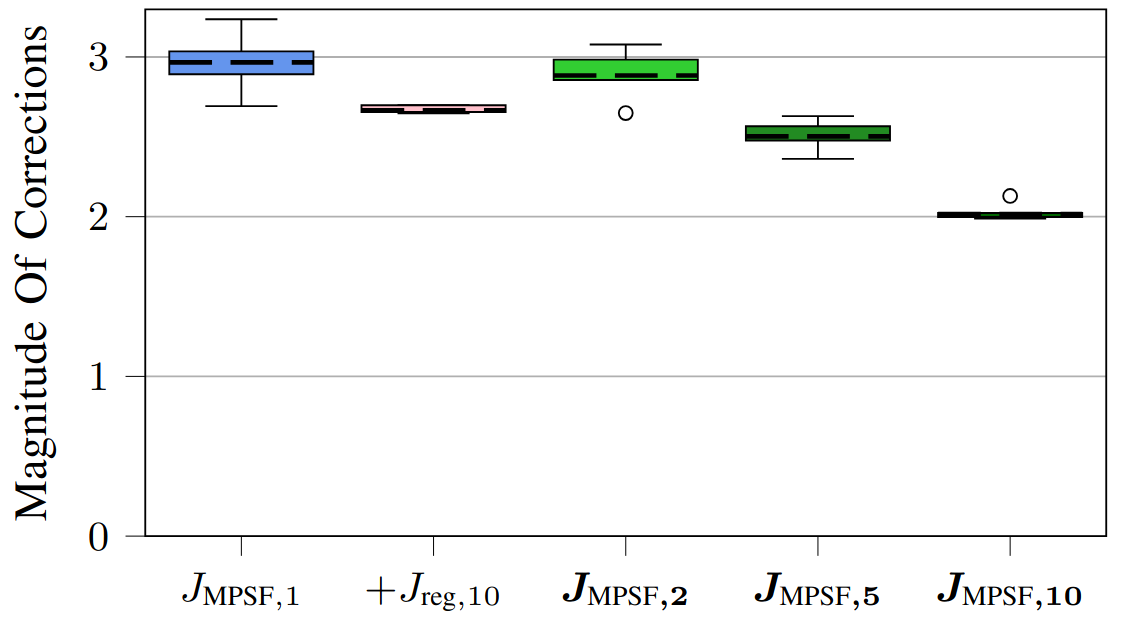

Fig. 1: Chattering caused by the standard one-step MPSF versus the multi-step MPSF. The multi-step filter reduces the peak-to-peak amplitude of chattering from 16.3cm to 3.6cm.

1.1 - Motivation

Safety filters impart hard safety guarantees to controllers, including deep learning controllers [1]. Model predictive safety filters (MPSFs) are a category of safety filters that leverage model predictive control (MPC) to predict whether uncertified (i.e., potentially unsafe) inputs sent from the controller will violate the constraints. In the case of a potential future constraint violation, the MPSF determines the minimal deviation from the uncertified input that results in constraint satisfaction.

Despite strong theoretical guarantees, MPSFs may cause chattering and high-magnitude corrections. Chattering occurs when the controller directs the system towards a constraint boundary and is repeatedly stopped by the safety filter. This leads to jerky and oscillatory behaviour, degrading performance and potentially causing constraint violations.

1.2 - Method

The standard (one-step) safety filter objective function is [1]:

$J_{\text{SF},1} = \|\pi_{\text{uncert}}(\textbf{x}_k) - \textbf{u}_{0|k}\|^2,$

where $\textbf{x}_k$ is the state at time step $k$, $\pi_{\text{uncert}}$ is the RL policy, and $\textbf{u}_{0|k}$ is the input to be applied (the optimization variable). By generalizing to multiple steps, the filter can minimize corrections over a longer prediction horizon:

$J_{\text{SF},M} = \sum_{j=0}^{M-1} w(j)\| \pi_{\text{uncert}}(\textbf{z}_{j|k}) - \textbf{u}_{j|k} \|^2,$

where $w(\cdot) : \mathbb{N}_{0} \to \mathbb{R}^+$ calculates the weights associated with the $j\text{-th}$ correction, $M$ is the filtering horizon, $\textbf{z}_{j|k}$ is the estimated future state at the $(k + j)$-th time step computed at time step $k$, and $\textbf{u}_{j|k}$ is the input at the $(k + j)$-th time step computed at time step $k$. The inputs are the optimization variables. This allows the agent to proactively correct actions to avoid unsafe states.

Contributions: We propose generalizing the standard safety filter objective function to minimize corrections over a horizon. We apply this approach to model predictive safety filters (MPSFs) and prove our approach inherits the theoretical recursive feasibility guarantees of the underlying MPC. We demonstrate this multi-step approach reduces chattering, jerkiness, and other potentially unsafe corrective actions.

1.3 - Results

To determine the efficacy of the proposed multi-step MPSF, we ran experiments on a simulated cartpole in the safe learning-based control simulation environment $\texttt{safe-control-gym}$ [2] and on a real quadrotor, the Crazyflie 2.0. The underlying MPC is a robust nonlinear MPC formulation [3]. The experiments test the standard one-step MPSF compared to our proposed multi-step MPSF with $M=2, 5, 10$. Additionally, we consider the one-step MPSF with regularization $J_{\text{reg}}$.

1.3.1 - Simulation Experiments

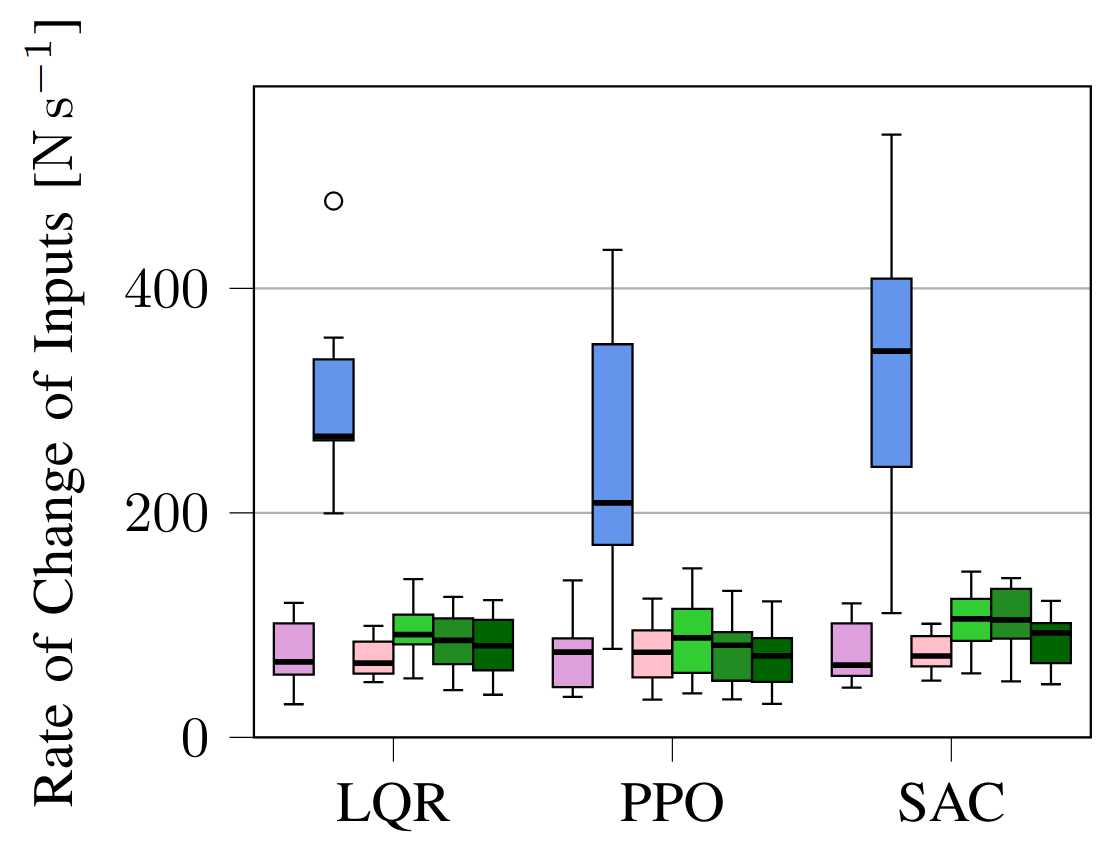

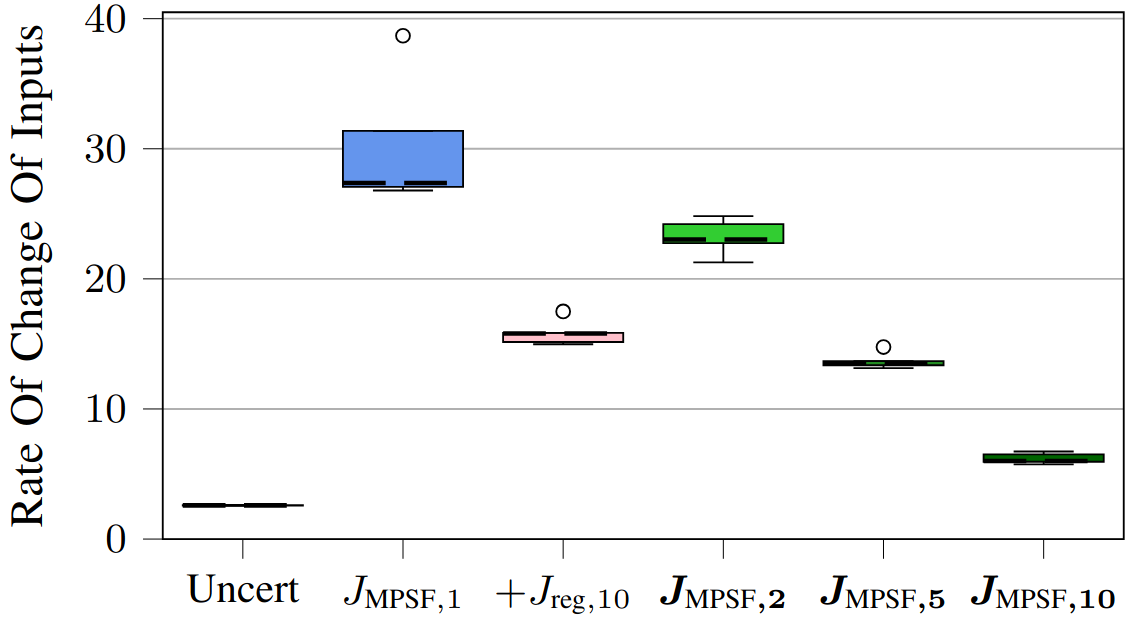

Fig. 3: Results for simulated experiments on a cartpole testing the multi-step approach.

1.3.2 - Real Hardware Experiments

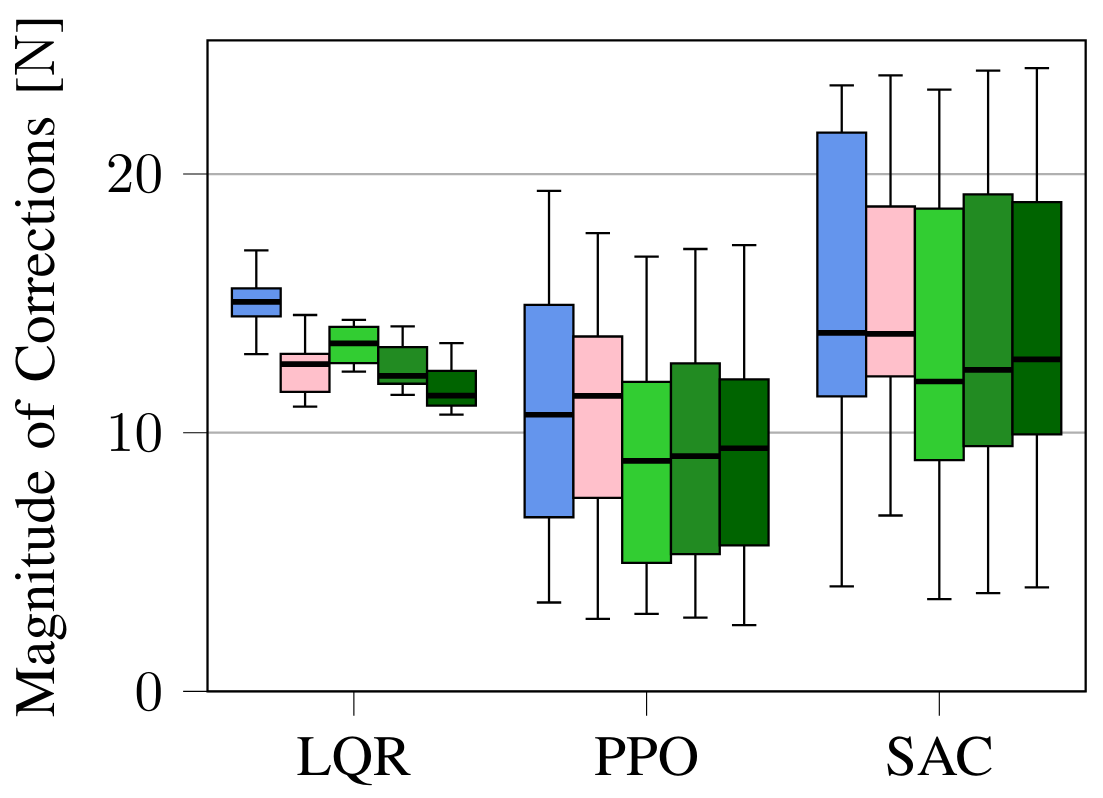

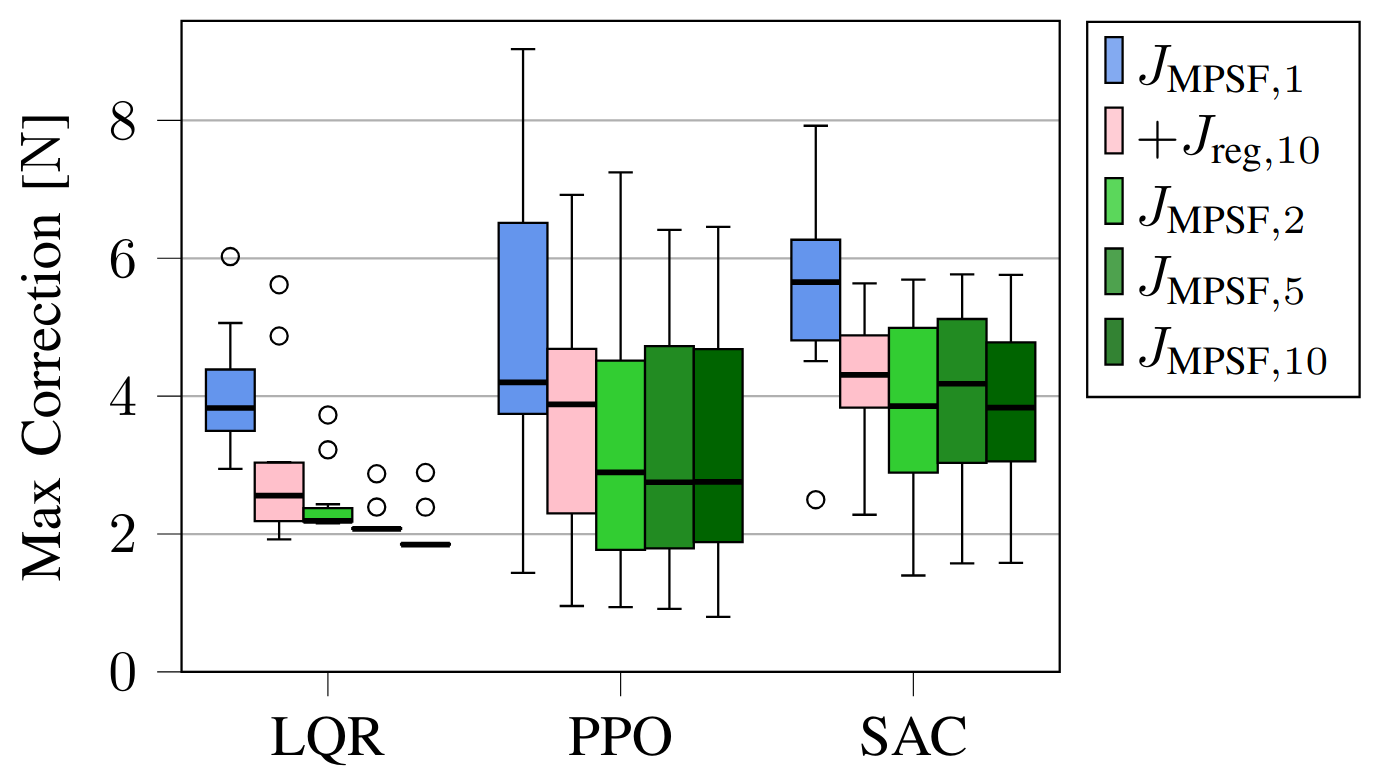

Fig. 4: Results for real hardware experiments on a Crazyflie 2.0 quadrotor testing the multi-step approach.

2 - RL Training with Safety Filters

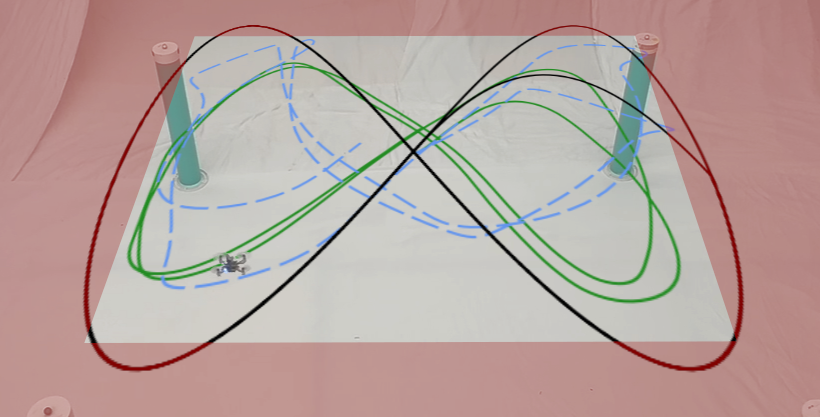

Fig. 2: An RL controller trained without a safety filter (blue) tracks a reference trajectory (black), but unforeseen interactions with the safety filter cause poor tracking. When trained with a safety filter (green), the behaviour is smoother and more performant. The constraints are in red.

2.1 - Motivation

Contributions: In this paper, we analyze three modifications to the training process of any RL controller through the incorporation of a safety filter. These modifications can be combined or used separately and can be applied to any RL controller and safety filter. We found that the modifications significantly improve sample efficiency, eliminate constraint violations during training, improve final performance, and reduce chattering on the certified system.

2.2 - Methods

2.2.1 - Filtering Training Actions

During training, the controller generates uncertified actions $\textbf{u}_{\text{uncert}, k} \in \mathbb{U}$. By applying the safety filter $\textbf{u}_{\text{cert}, k} = \pi_{\text{SF}}(\textbf{x}_{k}, \textbf{u}_{\text{uncert}, k})$, safety is guaranteed during training [4], improving sample efficiency by focusing on safe areas. Additionally, this maximizes the return on the final certified system on which it will be evaluated.

2.2.2 - Penalizing Corrections

We can penalize corrections during training to encourage the RL to execute safe actions [4]. The magnitude of the correction measures how unsafe the action was. Thus, we penalize the reward by $\alpha \|\textbf{u}_{\text{uncert}, k} - \textbf{u}_{\text{cert}, k} \|_2^2$, where $\alpha > 0$ is a tuneable weight. This reduces corrections and thus reduces chattering and jerkiness.

2.2.3 - Safely Resetting the Environment

Sample efficiency can be improved by using the safety filter to avoid initiating an episode in an unsafe state. We will sample $\textbf{x}_0 \sim \mathbb{S}$, where $\mathbb{S}$ is the set of starting states, and then determine the feasibility of certifying an input from that state. If the safety filtering optimization is feasible, $\textbf{x}_0$ is safe. If infeasible, another starting state is randomly generated until a feasible starting state is found.

2.3 - Results

The controllers were evaluated on a simulation of a Crazyflie 2.0 using the $\texttt{safe-control-gym}$ [2] and a real Crazyflie 2.0 [5]. The trajectory tracking task consists of tracking a figure-eight reference in three dimensions. The position is constrained to be 5% smaller than the full extent of the trajectory.

2.3.1 - Simulation Experiments

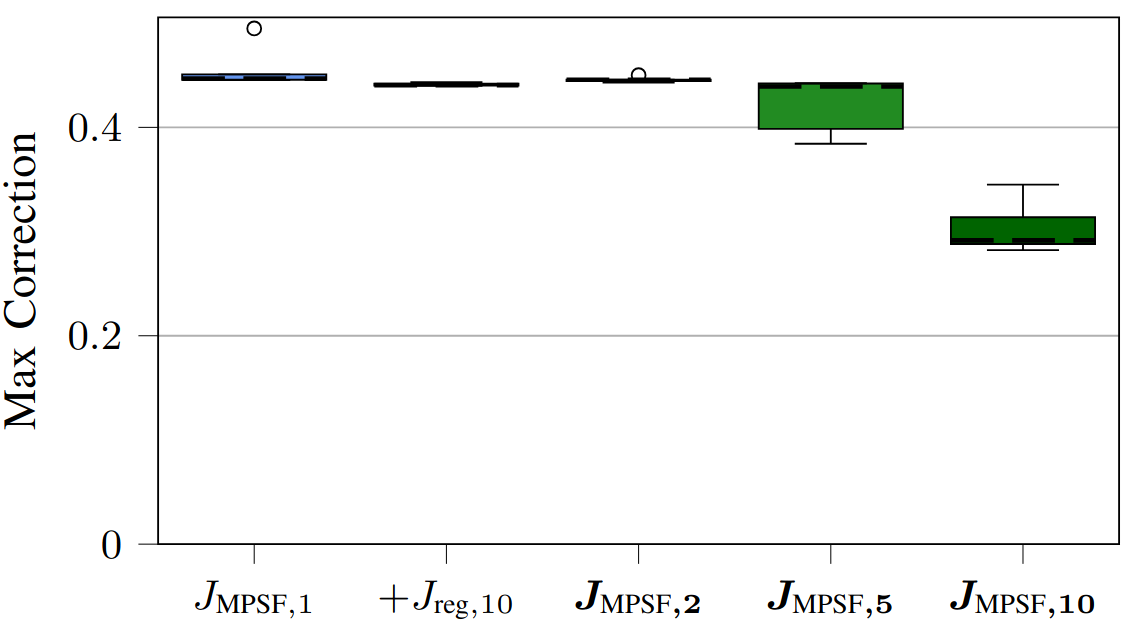

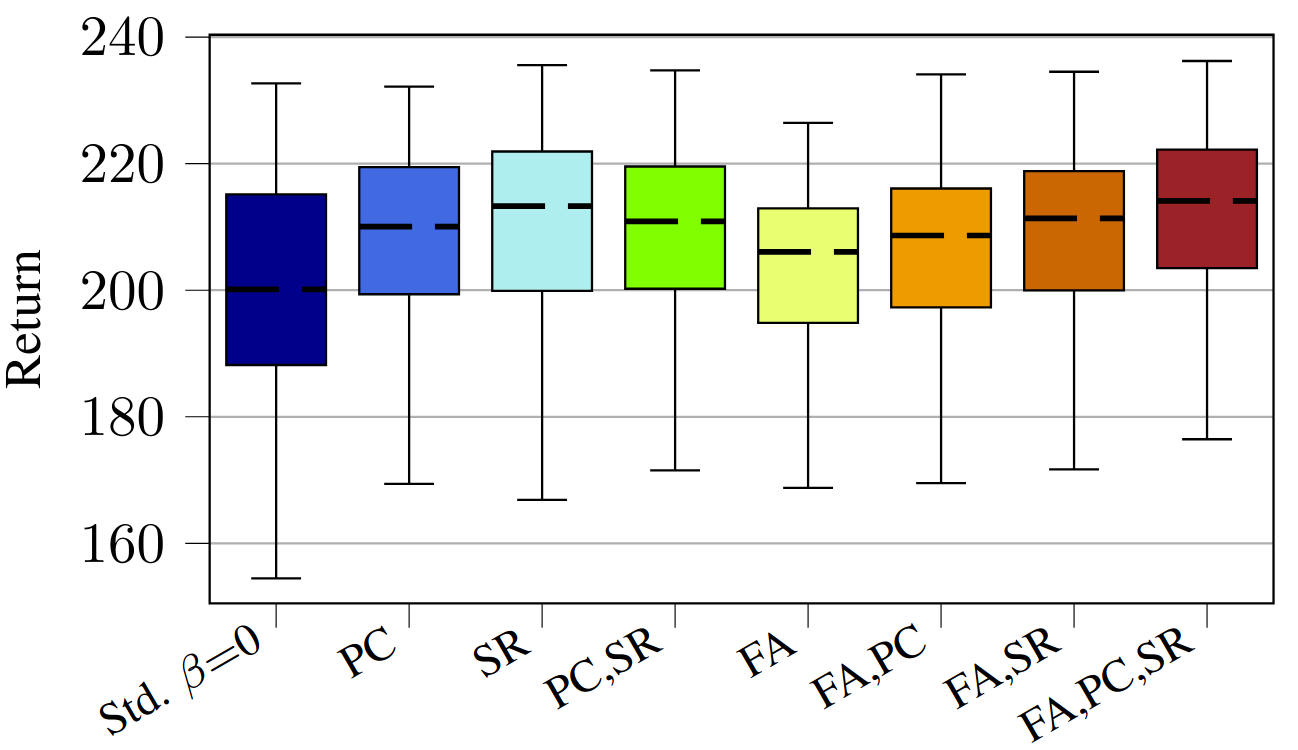

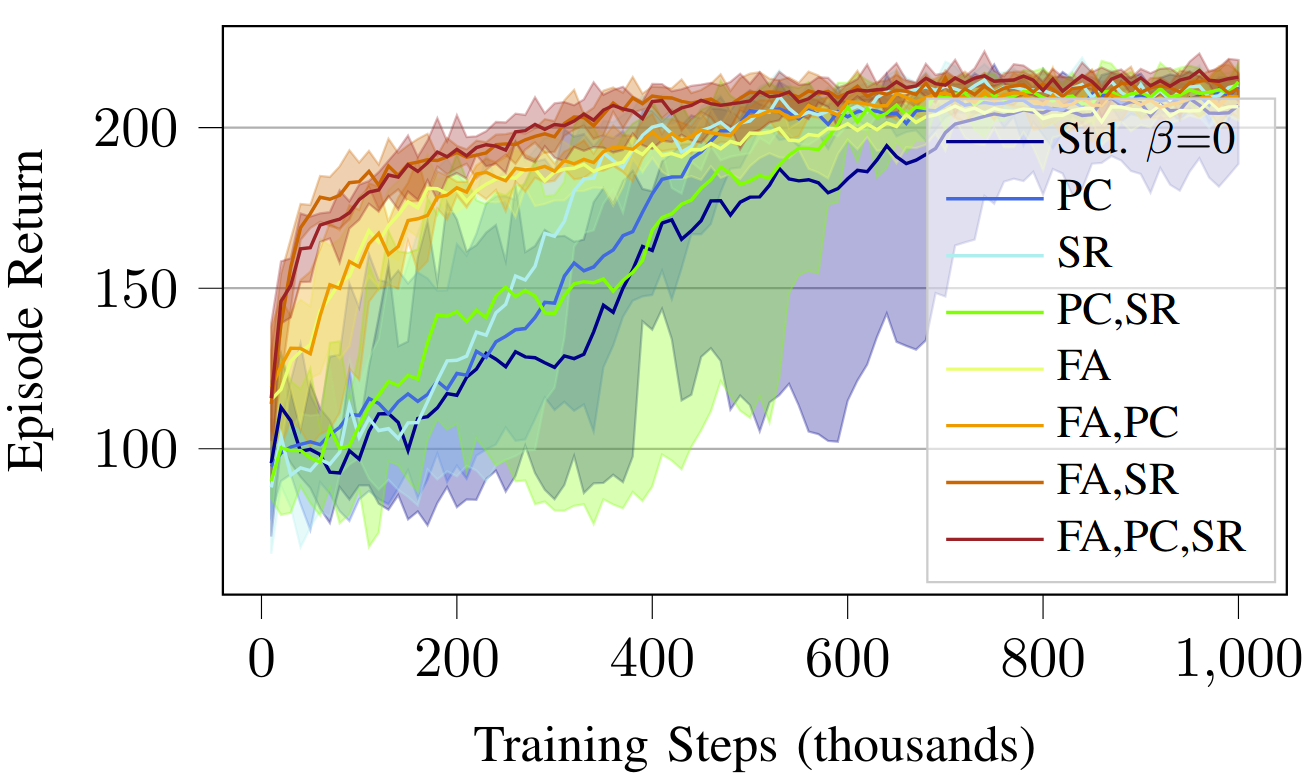

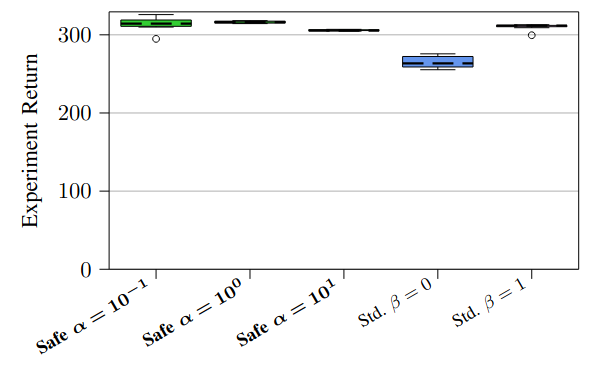

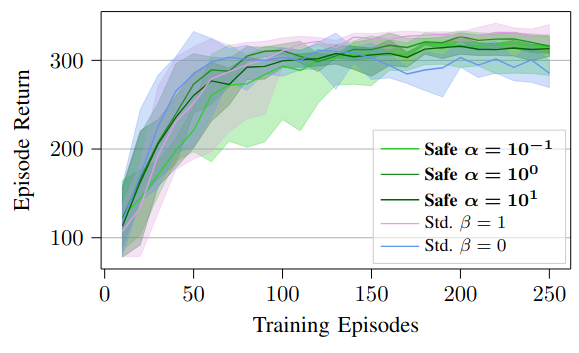

Fig. 5: Results for simulated experiments on a Crazyflie 2.0 quadrotor testing the various training modifications.

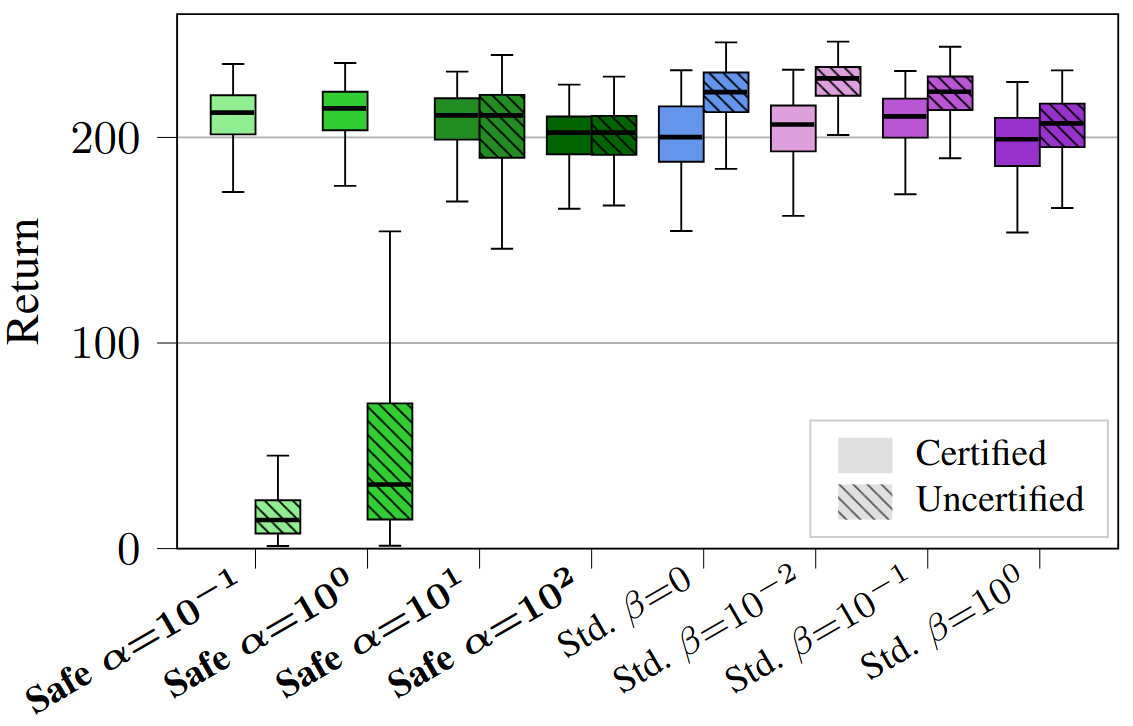

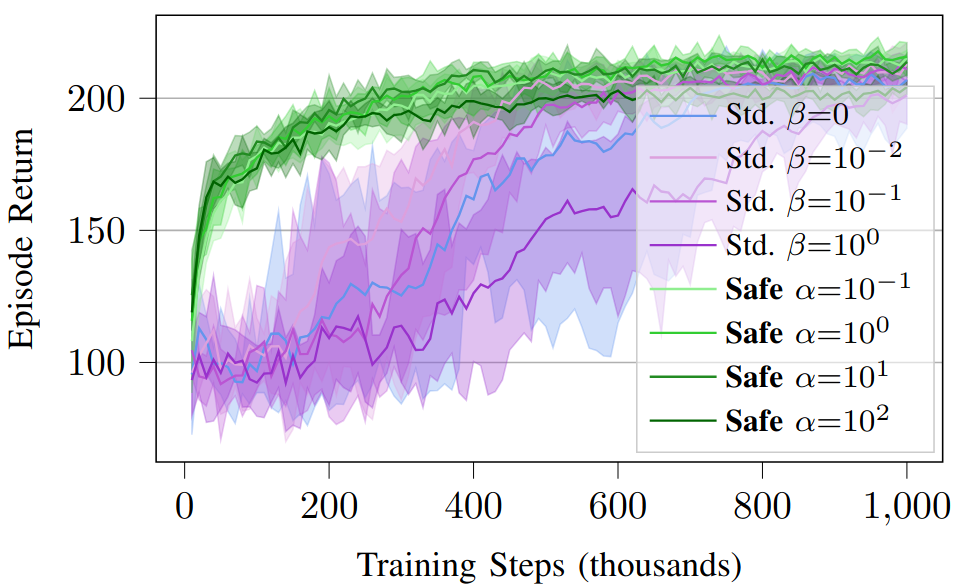

Fig. 6: Results for simulated experiments on a Crazyflie 2.0 quadrotor testing the effects of the correction penalty weight $\alpha$ and the constraint violation penalty $\beta$.

2.3.2 - Real Hardware Experiments

Fig. 7: Results for real hardware experiments on a Crazyflie 2.0 quadrotor testing the combined training modifications.

Watch the Full Video

BibTex

Multi-Step Safety Filters

@inproceedings{multi-step-mpsfs,

author={Pizarro Bejarano, Federico and Brunke, Lukas and Schoellig, Angela P.},

booktitle={2023 62nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC)},

title={Multi-Step Model Predictive Safety Filters: Reducing Chattering by Increasing the Prediction Horizon},

year={2023},

pages={4723-4730},

doi={10.1109/CDC49753.2023.10383734}

}

Safety Filtering While Training

@article{sf-while-training,

author={Pizarro Bejarano, Federico and Brunke, Lukas and Schoellig, Angela P.},

journal={IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters},

title={Safety Filtering While Training: Improving the Performance and Sample Efficiency of Reinforcement Learning Agents},

year={2025},

volume={10},

number={1},

pages={788-795},

doi={10.1109/LRA.2024.3512374}

}

References

[1] L. Brunke, M. Greeff, A. W. Hall, Z. Yuan, S. Zhou, J. Panerati, and A. P. Schoellig, “Safe learning in robotics: From learning-based control to safe reinforcement learning,” Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems, 2022.

[2] Z. Yuan, A. W. Hall, S. Zhou, L. Brunke, M. Greeff, J. Panerati, and A. P. Schoellig, “$\texttt{safe-control-gym}$: A unified benchmark suite for safe learning-based control and Reinforcement learning in robotics,” IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 2022.

[3] J. Köhler, R. Soloperto, M. A. Müller, and F. Allgöwer, “A computationally efficient robust model predictive control framework for uncertain nonlinear systems - extended version,” IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 2021.

[4] H. Krasowski, J. Thumm, M. Müller, L. Schäfer, X. Wang, and M. Althoff, “Provably safe reinforcement learning: Conceptual analysis, survey, and benchmarking,” Transactions on Machine Learning Research, 2023.

[5] S. Teetaert, W. Zhao, et al., “A remote sim2real aerial competition: Fostering reproducibility and solutions' diversity in robotics challenges,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.16743, 2023.